The Influence of Seafaring History on Modern Menswear

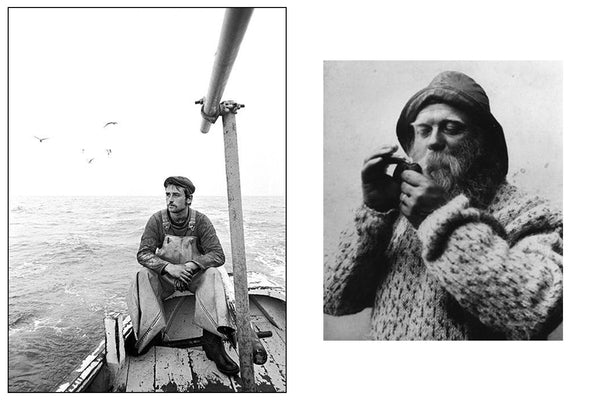

If you trace modern menswear back to its sources, you keep hitting water. Long before “heritage” became a mood board term, seafarers and dock crews were solving real problems with clothing: cut the wind, shed the spray, move without snagging, survive the day. What endured weren’t trends, but solutions—which is why the pieces we reach for now still look suspiciously like the gear that kept men alive a century ago.

Take waxed jackets. The idea—make cloth repel weather—started when North Sea crews learned to treat sailcloth so it stayed lighter and faster in foul weather; offcuts became capes and slickers. By the late 19th century, mills in Britain were purpose-finishing cotton with wax, turning seaborne improvisation into durable outerwear. Names like Halley Stevensons (Dundee, since 1864) and British Millerain (est. 1880) helped standardize the process; what began as oilskin experiments evolved into stable, rewaxable cotton that could take a beating and then take another. Function came first; the patina we prize now was a by-product.

Wool solved a different problem: staying warm when the weather didn’t cooperate. Along Atlantic coasts, fisherman sweaters — dense, resilient knits—were engineered for wet, punishing work. The romance around every cable pattern serving as family ID is just that—romance—but the core truth remains: lanolin-rich wool, tight gauges, and practical stitch structures kept crews working. Today’s wool sweaters (from sturdy shawl cardigans to pared-back crews) still lean on that physics: warmth that breathes, structure that holds shape, texture that earns its keep.

Uniforms pushed those same ideas into everyday dress. In the early 1900s, the U.S. Navy formalized work uniforms that were meant to be abused: denim dungarees and chambray shirts for jobs where dress blues made no sense. Denim wasn’t “born” in the Navy, but naval adoption—dungarees officially authorized as working dress by 1913, chambray in service from the 1910s onward—helped cement both fabrics as American workwear standards that later migrated ashore. When a garment is issued because it works, it tends to stick around.

The Navy also birthed one of menswear’s most quietly influential layers: the CPO shirt. Issued to Chief Petty Officers in the 1930s in robust wool flannel, it was cut to move, warm enough to throw over a knit, and tough enough for deck duty. Swap the insignia for civilian buttons and you have the template for the modern shirt jacket: neat, practical, and endlessly useful.

What’s striking is how these maritime answers outlived their original contexts. Waxed cotton left the docks for country lanes and city commutes, precisely because it still does the job. Heavy knits became weekend mainstays for the same reason. Naval dungarees, chambray, and CPOs morphed into the backbone of men’s outerwear and everyday uniforms; not because of nostalgia, but because garments refined under real pressure rarely need re-invention.

This is the quiet law behind “timeless”: when form grows out of function—when a jacket must shed rain, when a knit must insulate wet, when a shirt must take abrasion and wash out easily—the silhouette that survives is the one that works. It’s why waxed jackets, fisherman sweaters, and naval-born layers still anchor modern closets, and why contemporary interpretations (a maritime-leaning jacket, a CPO-inspired overshirt, a fisherman shawl cardigan) feel current without trying. The grit and natural materials that once kept crews at sea now offer something rarer on land: reliability.

A century on, we’re still wearing the sea—sometimes literally (waxed cotton that needs a seasonal re-wax), sometimes in spirit (dense wool that holds its shape, denim and chambray that clean up and carry on). The aesthetics endure, but only because the utility does. And that, more than any story, is what makes these pieces timeless.